Amanita Muscaria, or the Fly Agaric, the iconic and quintessential mushroom (or toadstool) of European folklore, is one steeped in much myth and legend, both urban and otherwise. Some (mostly mis-informed) people have been brought up with the belief that it is deadly poisonous, others believe it to be the Soma, the sacrament of the Gods, of the Indo-European Aryans and later the Hindus and the Ancient Greeks. This is a fungus that is embedded in human culture and symbolises many things to many people.

Other common myths about this mushroom exist: did the Viking bezerkers truly partake in the fungal fruiting body in order to fuel their animalistic raping and pillaging of hapless Celts, Anglos, Saxons, Slavs etc. on their conquests across Europe? Did, as urban legend suggests, the mushroom inspire the myth of Santa Claus, with his red coat, flying reindeer and magic ability to descend down chimneys and leave gifts for good girls and boys, or coal for the naughty ones?

As it is approaching Christmas, I will be focusing here on the Santa Claus myth, an analysis of Viking bezerkers can wait for the New Year.

Written by Forager Matt

To those unfamiliar with the association between a “poisonous” red toadstool and Ol’ Saint Nick, I will outline the myth first.

I have seen the repeated claim, in conversation, online and in literature, that the Fly Agaric mushroom has inspired the modern day representation of Santa Claus/Father Christmas. The claim is repeated with the following evidence:

–Sami herdsmen, whose range of territory spans much of the North Pole, including parts of Finland and Russia, apparently have a tradition of shamanic use of this mushroom. Reindeer favour the red-capped fruiting bodies as an autumn snack, and have been observed to eat these mushrooms and fall prone to excitatory behaviour, jumping up and down, “prancing”, generally becoming more animated. Herdsmen observed this, and wanted to experience the effects of the mushrooms themselves. Over time, they learnt that drinking the urine of a reindeer that had ingested the mushroom, avoiding nausea and other unpleasant side effects associated with eating it raw. It is also rumoured that shaman with strong enough constitutions would eat the mushroom first, dispensing their urine with the now-metabolised Muscimol to their companions to drink.

–The mushrooms were sometimes dried, strung up and used to decorate fireplaces and Christmas trees over Yule (before Christmas was even known as Christmas, given that Christ has to be born in order to give his name to the festivity), given they are usually found in October/November, December ends up as the prime time of year to display these charming dried caps as decoration.

These purported cultural uses for the mushroom are said to then combine to influence the myth of Santa Claus. The flying reindeer are inspired by the jumping, muscimol-drunk reindeer observed by the Sami. Santa Claus coming down the chimney to leave gifts is influenced by the practice of decorating fireplaces with dried Amanita caps, as well as the flying and descending of the Shaman through the open roof of his yurt. The red and white coat is inspired by the vivid red and white fruiting bodies of the mushroom, perhaps also mimicked by the dress of the shamans who ingested these fungi to experience the feeling of “flight”, whilst potentially also dressed in red and white.

I read these myths and digested them without further critical thought. What fun, that another iconic piece of Christmas iconography can be traced back to some kooky European tradition of drinking reindeer piss to receive visions of enlightenment.

Later I had another thought.

Hang on, didn’t Coca Cola give Santa his red coat in the 1950s? I thought he was supposed to be green before that?

In which case, how did the Fly Agaric influence any of this?

I found myself in a deep-dive on Christmas tradition to dissect this further. Did, as urban legend suggests, the iconic mushroom of European folklore actually influence our modern Santa? Let us examine.

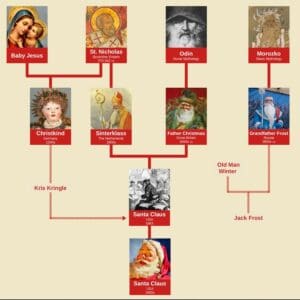

St Nicholas, Father Christmas and Santa Claus

St Nicholas of Myra – By Jaroslav Čermák – Galerie Art Praha, Public Domain

St Nicholas of Myra – By Jaroslav Čermák – Galerie Art Praha, Public Domain

I thought examination of this subject would be easy, google some stuff about St Nick, gather evidence, present, job done. It turns out that instead, I have to first of all examine the relationship between St Nick, Father Christmas and Santa to determine where the influence of the Fly Agaric might have ingressed into our cultural consciousness.

St Nicholas of Myra, of modern Greek descent, existed during the time of the Roman empire between 270 and 343 AD. He is the direct inspiration for Sinterklaas (the Dutch name), or Santa Claus as he is now known. Nicholas’ habit of secret gift giving gave rise to the folklore of Santa Claus [Michael the Archimandrite, Life of Saint Nicholas Archived 3 July 2018 at the Wayback Machine (Chapters 16–18)]. Saint Nicholas was not known for having owned reindeer (being Greek), climbing down chimneys, or wearing a red coat. The myths associated with him, although interesting stories, do not draw a link to Sami shamanism (although the Fly Agaric can be found in Greece too). We will discard the original St Nick as a possible option for inspiration-by-mushroom when it comes to folklore.

The Christian stories of St Nicholas then spread, along with other Christian stories, throughout Europe. Sinterklaas, based on St Nicholas, arose in the Netherlands and Belgium. As Dutch settlers made their way over to the New World (America), the name was carried over, and slowly evolved into the man we know now, Santa Claus. The name Santa became more common around the 18th century in America specifically [“Last Monday, the anniversary of St. Nicholas, otherwise called Santa Claus, was celebrated at Protestant Hall, at Mr. Waldron’s; where a great number of sons of the ancient saint the Sons of Saint Nicholas celebrated the day with great joy and festivity.” Rivington’s Gazette (New York City), 23 December 1773.]

Please note, I have not referred to Santa as Father Christmas during this passage. This is for good reason. Father Christmas evolved in Europe separately from St Nicholas/Santa. Father Christmas, usually dressed in green, with a wreath of holly around his head, was a personification of Christmas cheer common in Britain, far before the name Santa Claus was ever uttered by an Anglo/Saxon/Brit. It appears he was inspired by the Norse God Odin, who was celebrated at Yule (a mid-winter festivity enjoyed by Germanic tribes in Western Europe) [Baker, Margaret (2007 1962). Discovering Christmas Customs and Folklore: A Guide to Seasonal Rites Throughout the World, page 62. Osprey Publishing.]. Yule-tide celebrations and culture were later assimilated into what is known as Christmas, due to Christian tradition spreading and merging with the older pagan practices across millions of newly converted Europeans.

1848 depiction of Father Christmas By Alfred Henry Forrester – The Illustrated London News, Public Domain,

Odin is speculated to have influenced Father Christmas (not Santa) because of his long white beard, blue hooded cloak and practice of taking to the skies on his eight-legged steed, Sleipnir, visiting people with gifts. Later, this evolved into the green (sometimes red)-cloaked Father Christmas. Could inspiration from the mushroom lie behind the Odin myth? It is possible albeit tenuous – most summaries of the Yule myths surrounding Odin don’t mention mushrooms, without further research into source texts I am unable to validate if they feature prominently in the myths or not.

Santa Claus, having evolved separately from Father Christmas, arrived in Britain in the late 1850s. The two characters then merged over time, combining origins of the Christian myth of St Nicholas, with that of the Norse/pagan Odin. Father Santa-Christmas-claus was depicted in a number of coloured cloaks, ranging from green to red to blue to brown. As the popular story goes, the Coca Cola company portrayed Santa Claus in red in an advertising campaign in the 1930s. Before this, the Santa character had been displayed in red/white of several covers of Puck magazine, even earlier than 1930 [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Santa1902PuckCover.jpg]. This shows that Coca Cola, contrary to the urban legend that attributes Santa’s modern appearance to them and them alone, were in fact just solidifying the already existing aesthetic of a growing cultural figure.

Our first problem

We come to our first issue with our Fly Agaric urban legend. The claim that the shamanic tradition of using Fly Agaric over winter, as both soul-medicine and as decoration, directly influenced our modern Santa/Father Christmas in terms of his style of dress, namely the red cloak.

As we have examined, both characters that combined to create our modern Mr Claus, have appeared throughout history in a manner of different colours, red has not been the only one.

Santa Claus (depicted most commonly in red, unlike Father Christmas, who more commonly wore green) is the myth that stems from St Nicholas, a Greek, Christian saint. Although the story of St Nicholas swept Europe as far as the Netherlands, it does not appear to have blended with any obvious aspect of European paganism, the most likely carrier of any tradition closely associated with ritual use of the Fly Agaric. If anything, we would expect to see this influence more heavily from the Norse God Odin, who was the root of Father Christmas. Odin however, as we have examined, was depicted in a blue cloak, riding an eight-legged flying steed, NOT a reindeer. The character of Father Christmas, before his merging with Santa, was not depicted as having flown with reindeer either.

Despite claims of numerous articles on the internet that embellish this myth with extra detail that strengthens the relationship of the Fly Agaric to the Odin myth, at the time of writing, I cannot find any firm sources to suggest this is the case. I am happy to adjust this viewpoint in the face of real evidence (i.e. evidence that is not a potential fabrication of 20th/21st century neo-folklore).

This leaves us in a difficult position, as the evidence we have shows that both sets of myth contain a jolly man in some form of cloak, but the colour of his cloak does not become ubiquitous until the early 20th century. This leaves only a very tenuous link between the colour of Santa’s dress and the red and white cap/stem of the Fly Agaric, a subtle influence may still remain somewhere, but there are far too many factors involved, far too many disparate origin stories, both cultural and geographical, to say for certain that Amanita Muscaria had any influence on the colour of Mr Claus’ red and white uniform.

Oh deer oh deer – problem number 2

Next up, we examine the reindeer. As mentioned, it is a fact that reindeer enjoy Amanita Muscaria as a stimulating snack.

It is stated in urban legend that the flying reindeer in our Christmas story are inspired by tales of deer, excited and intoxicated by a mycologically-created cocktail of ibotenic acid and muscimol, which were then used by Northern European shaman to also “fly”.

In this case, we should see the tales of flying reindeer date back to the near-origins of at least one of our proto-Santa myths, given that the ingestion of these mushrooms will have been happening for hundreds of thousands of years under the watchful eye of nomadic herders throughout a multitude of generations.

According to the sources examined, again, the St Nicholas à Sinterklaas progression shows no sign of flying reindeer, or indeed any other sort of flying herbivores. Our Germanic Odin à Father Christmas myth shows some more promise, in that it does depict a flying, eight-legged horse, but again this is a far cry from a sleigh pulled by nine reindeer. The trail again runs cold, as by the 1800s, the British Father Christmas was not depicted as being accompanied by any sort of flying animal.

It is in 1821, that an American poem “Old Santeclaus with Much Delight” [“mentioning Don Foster, Author Unknown: On the Trail of Anonymous (New York: Henry Holt, 2000: 221–75) for the attribution of Old Santeclaus to Clement Clarke Moore”. Tspace.library.utoronto.ca. Archived from the original on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 21 December 2010.], described Santa Claus on a reindeer sleigh, bringing gifts to children. The poem is anonymous, so unfortunately it is not possible to investigate the author so see where this inspiration arose from. This is likely from exposure to Northern tribes of Native Americans or Inuit, who may have provided inspiration for the sleigh to appear in this poem. There may have been folk-stories already revolving around Santa and Reindeer at this time, it is unlikely that a New York poet was the first person on the planet to think of this, but it does appear that the depiction of Santa in a sleigh, drawn by reindeer, was uncommon until this point. Moreover, the idea comes from a region that is unlikely to have much exposure to Northern European paganism or shamanic practice. Fly Agaric use appears to be far more common in European folklore than American.

Once again this leaves our urban legend in murky waters. Given the evidence, it is quite unlikely that reindeer ingesting Amanita mushrooms are responsible for the depiction of flying reindeer in our modern version of Santa Claus. From the pagan origins of Father Christmas, Odin’s flying steed does not make it into even semi-contemporary portrayals of the jolly personification of Yuletide/Christmas. From the saintly origins of Santa Claus, no flying reindeer feature in portrayals until around 1820, these originate in New York USA and cannot, without potentially a lot more sleuthing into the matter (including discovering the identity of two anonymous poets) be directly attributed to a shamanic or mycological origin.

So where does this lead us?

Having researched this matter, two pints deep on a Saturday evening, without much better to do, I can conclude, in my role as amateur historian and professional forager, that the influence of the Fly Agaric mushroom on Santa Claus/Father Christmas myth is negligible at best. The urban legend, in my opinion, is bunk, without seeing a great deal of supporting evidence to the contrary.

The legend is repeated over and over, seemingly without a chain of actual historical literature to suggest how the Santa Claus character derived his red cloak and flying reindeer from shamanic use of Amanita Muscaria. The evidence explored in this text shows instead, that our modern Santa Claus was derived from a mix of Christian and pagan mythology, without the direct influence of any mushroom. The pagan mythology, being the most likely source of influence regarding use of fungal entheogens, comes up empty, with the white-bearded Odin traditionally wearing a blue cloak and riding on a flying steed, which did not enter the later depictions of Father Christmas. Any myth that precedes Odin is murky at best in providing evidence for our Agaric myth.

The Christian myth leads us to the development of Santa Claus in 19th century America, where his cohort of Reindeer are then introduced by writers in New York. His red cloak was prone to colour change, before finally settling on the colour red due to the expanding influence of advertising and colour media in the 20th century.

Am I saying it is totally impossible that the Fly Agaric influenced the Santa myth? Of course not. I cannot say this for certain, and there is still room for evidence to the contrary. However, that evidence has not come to light in this limited investigation (using only secondary sources I could find online). Myth not entirely busted, but certainly not as plausible as expected.

On this note, I bid you farewell, dear Reader, and wish you a Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year. I hope Father Christmas (or Santa to you Yanks) gifts you with a bountiful forage come spring, and the chance to glimpse some glistening red Amanita caps come Autumn.