Reedmace (Bulrush) / All Year / Edible

I often find Reedmace around golf courses, the big cigar tops sat on shoots are the most obvious way to see them. There’s a couple of good edible parts to enjoy.

Common Names

Reed mace, bulrush

Botanical Name

Typha latifolia

Scientific Classification

Kingdom – Plantae

Order –Poales

Family – Typhaceae

Physical Characteristics of Reedmace

An aquatic or semi-aquatic perennial plant 1.5 to 2.5m tall.

Leaves

Leaves 10-20mm wide. The leaves are fleshy, greyish green and flat, resembling giant leeks at first.

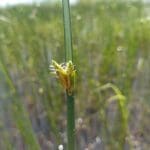

Flowers

As the flower spikes grow the leaves form a protective sheath around the flowering stem.

The flower spikes are made up of tiny, petal-less flowers. The numerous male flowers form a narrow spike at the top of the vertical stem. Each male flower is reduced to a pair of stamens and hairs. In June the male parts swell and produce a mass of yellow pollen that drops on to and fertilises the many female flowers, which form a dense, sausage-shaped spike on the stem below the male spike. When fertilised the female flowers turn a rich chocolate brown.

Seeds

The seeds are minute, 0.2 millimetres (0.008 in) long, and attached to fine hairs. When ripe, the heads disintegrate into a cottony fluff from which the seeds disperse by wind.

Habitat

Up to 500m Found in most lowland areas of England and Wales. In Scotland it is widespread in the Borders and North of the Southern Uplands but absent in higher-altitudes. Widespread in Ireland but more sparsely distributed in higher altitude areas.

Often in large clumps on the edge of ponds, lakes or slow-moving rivers; also in dykes, canals and streams.

Known Hazards

Be sure to check the water quality where the Reedmace is growing as any contaminants will be absorbed by the plant. Do not eat the rhizomes raw in case of contamination. Also, take care when extracting the plant from the water not to expose the flesh to any bacteria present in the mud.

Could be Confused with

The Yellow Iris and Stinking Iris have flat leaves for their entire length so that the bases of the leave bundles are oval in cross section whereas those of the Reedmace are round. Lesser Reedmace has narrower leaves with curved backs and thinner flower spikes and a gap between male and female parts. Lesser Reedmace is also good to eat.

Edible Uses

Reedmace has been eaten by cultures all over the world. The pollen can be used as flour and a corn flower substitute can be extracted from the pulp of macerated rhizomes. The flour has a higher mineral content than any flour except potato and has more protein than rice or maize.

When the leaf bundles are about 1m high, feel the bases to check whether the flower stem has started to develop – if it has it will be woody and inedible. Good ones will give a little when squeezed. Cut or break them off as near to the roots as you can – This is what is referred to as the heart.

Hearts are prepared by removing any tough parts of the leaves and boiling or steaming the tender, white inner section. When sliced thinly they show the intricate inner structure of the plant which is very attractive. Serve with a little butter or light sauce or use in salads.

The whole flower and portion of the stem beneath can be eaten when very young and tender. Blanch and use in warm salads.

Notes on Herbal uses

The plant has been widely used in traditional and modern medicine, For example the leaves have been mixed with oil and used as a poultice on sores.

The dried pollen is said to be anticoagulant, but when roasted with charcoal it becomes haemostatic. It is used internally in the treatment of kidney stones, haemorrhage, painful menstruation, abnormal uterine bleeding, post-partum pains, abscesses and cancer of the lymphatic system.

Externally, it is used in the treatment of tapeworms and diarrhoea.

The roots are pounded into a jelly-like consistency and applied as a poultice to wounds, cuts, boils, sores, carbuncles, inflammations, burns and scalds

The flowers are used in the treatment of a wide range of ailments including abdominal pain, cystitis, and vaginitis. The young flower heads are eaten as a treatment for diarrhoea. The seed down has been used as a dressing on burns and scalds.

It should not be prescribed for pregnant women.

Extra notes from the Foragers

The Reedmace is nowadays often called the Bulrush. However, the true Bulrush is actually another species entirely: Scirpus Lacustris.

There are many theories as to how the confusion came about. Often blamed is the Victorian artist Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema, for included them in his painting Moses in the Bulrushes. This appears to be a folk-myth: Sir Lawrence doesn’t appear to have produced a painting entitled Moses in the Bulrushes. He did paint The Finding of Moses but there is not a Reedmace to be seen.

Around the same period, however, illustrations of this story were given away at Sunday schools. Some of these do indeed feature the distinctive sausage-shape of Typha latifolia. It may be that these – and not Sir Lawrence – are the original culprit!

As the Reedmace leaf and flower spikes emerge from the water they provide a route for dragonfly and damselfly larvae to emerge from the water. The bushy bases offer them shelter from predators like newts, frogs, toads, shrews and water voles.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.