Lichens are fascinating symbiotic associations between a fungus (mycobiont) and a green alga or cyanobacterium (photobiont). Through this blog post we’re going to be looking at lichens as food.

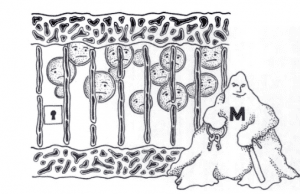

This relationship can range from mutualism to controlled parasitism. Although the Fungal element of the Lichen does no obvious harm to the photobiont element, make no mistake, the photobionts cannot escape.

What you see when you look at a Lichen is a thallus produced by the fungus. The thallus or body contains the photobionts (algae or cyanobacterium) within it. The photobionts are protected from drying and excessive light and in return the fungus can access a carbon source.

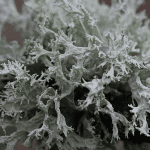

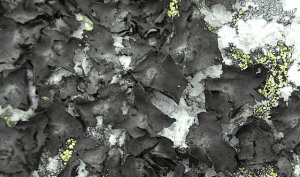

Lichens are divided into three groups. Foliose Lichens that look slightly leafy such as Tree Lungwort (Lobaria sp.), Fruticose Lichens that hang down a bit like a fruit would such as Old Mans Beard (Usnea sp.), and Crustose Lichens that form, yes you’ve guessed it, crusts on rocks and trees.

Foliose Lichen Fruticose Lichen Crustose Lichen

The oldest known true fossil record of a Lichen is early Devonian (about 400 million years ago) and was found in the Rhynie Chert beds in Aberdeenshire, Scotland.

There is a long history of use by Humans of Lichens, both as food, medicine, dyes and as landmarks for both their colour and appearance.

The earliest known reference to Lichens in Britain is a Cornish charter of c. 967 AD and describes of an area on the Lizard Peninsula,

“then along the way to cru draenoc (Thorny Barrow); then to carrecwynn (White Outcrop); then back again to pollicerr (now a farm called Polkerth)”

The white outcrop ‘carrecwynn’ refers to a stone outcrop that still carries the white coloured Lichen Ochrolechia parella. There are later descriptions of the area that refer to main mellyn (yellow rocks) that is thought to allude to the yellow Lichen Xanthoria parietina.

The Anglo Saxon record for the lead up to the Battle of Hastings in 1066 notes that King Harold asked his noblemen to meet him with their armies at the har (hoar) apple tree on Caldbec Hill. At that time in the English language har is used to describe a tree or stone that was grey and shaggy with Lichen. Har has morphed into hoar or hoary and can be found in expressions such as ‘hoarfrost’.

The har apple tree must have been a well-known landmark at the time and instruction to meet there would have been as clear as meeting under the clock in Waterloo station.

The use of Lichens for dyeing has been recorded as far back as the ancient Egyptians and is also mentioned in the Old Testament.

Lichens were used in Britain for dyeing both as a cottage industry and later, on a commercial scale, with the last cottage industry continuing right up to 1997 in Scotland.

Across the world, Lichens have been used as an ingredient in food and with the use by Rene Redzepi of Noma restaurant in Copenhagen (voted 1st in the worlds best 50 restaurants in 2014), Lichens are now used regularly by several chefs in the UK.

Admittedly the fact that they are traditionally served up semi predigested from the stomachs of Deer, (Umbilicaria spp. also known as rock tripe, are said to be sweeter consumed in this way), may be slightly off putting but then if most people knew what went in to a haggis or black pudding they may also think twice before eating it. Certainly the popularity of Scandinavian cuisine will have added to the current popular trend of using Lichens in dishes.

Lichens have been eaten traditionally for much longer though, particularly in China, Korea and Japan where there are several species that are popular, not just nutritionally, but also for their medicinal properties too.

Umbilicaria is referred to as Rock Ear in Chinese cuisine and Rock Mushroom in Japan. In India, Black Stone Flower, another Umbilicaria spp is regularly eaten.

Cladonia rangiferina, also known as Reindeer moss, is the species taken from the stomachs of reindeer and served in Scandinavian countries.

Bryoria fremontii, or Wila is still eaten by first nation American tribes. The Wila is left to soak first and then cooked. Wila is also used in the Scandinavian drink Aquavit.

In fact, several types of Lichen are now being added to beers instead of Hops, both for flavouring and in the past they will have also added medicinal qualities to the drinks. I regularly add Usnea Lichens to my forest brews.

Nutritionally Lichens contain carbohydrates, proteins, vitamins A, B1, B12, D3, iron, iodine, usinic acid, lichen acid and mucilage. Julia Schwarz, a graduate of The University of Arts in Vienna, has developed a range of food products using Lichens.

On a cautionary note, although most Lichens are thought to be edible, there are a couple out there that are definitely toxic to other mammals, so thoroughly research the species that you have found before embarking upon a culinary adventure with it. All Lichens contain acids so they will need to be boiled and rinsed before consumption and some also need to be soaked for a period of time too.

Traditionally Lichens were used to treat wounds, skin disorders, respiratory and digestive disorders and obstetric and gynecological issues. They are both antibacterial, antiviral and (conversely) antifungal. There is a growing body of research looking into various Lichens for use in the treatment of some cancers and it is thought that most Lichens have anti inflammatory properties and are antioxidant too.

References

Ahmadjian, V. The Lichen Symbiosis (Wiley, New York, 1993).

Taylor, T.N., Hass, H., Remy, W., and Kerp, H. 1995. The oldest fossil lichen. Nature 378:

244.

Gilbert, O. Lichens (Collins New Naturalist Library, Book 86, 2000)

https://www.britannica.com/science/fungus/Form-and-function-of-lichens#ref519271

https://www.finedininglovers.com/article/new-gourmet-trends-lichen

https://www.dezeen.com/2018/10/22/julia-schwarz-unseen-edible-food-lichen-vienna-design-week/

https://schwarzjulia.com/unseen-edible

https://arctichealth.org/media/pubs/297033/9783319133737-c2.pdf