In the 1990’s a highly pathogenic ascomycete fungus called Hymenoscyphus fraxineus or ash dieback and The Impact on Our Native Ash Population arrived in Europe from East Asia.

Ascomycete are known as sac fungi, because they produce their spores inside sacs. They form the largest phylum of fungi, with over 64,000 species that include Morels, Truffles, brewers and bakers Yeasts, Moulds, Mildews and the fungal component of Lichens.

Credit: Jeremy Inglis/Alamy Stock Photo

The disease is also known as Chalara Ash Dieback, which is useful, as it differentiates it from other pathogens which can cause dieback on Ash.

It spread across the continent, devastating Ash species, with Common Ash, Fraxinus excelsior, being particularly affected. Another mainland European Ash, the Manna Ash, (F.ornus), has been found to have only affected foliage so far, suggesting that it may have more resistance.

Chalara occurs on Asian Ash species but they seem able to tolerate infection with only mild symptoms on foliage, having evolved side by side across thousands of years.

It’s been found that young trees have little resistance to Chalara and quickly succumb, but older trees seem able to live with it for much longer. There is evidence to suggest few ash trees older than 20 years, die of ash dieback and that trees are just weakened to eventually die because of honey fungus or another secondary cause (Skovsgaard, 2009).

Ideas of how Ash Dieback arrived in Europe

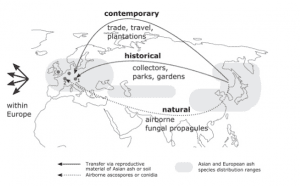

It’s not known exactly how it arrived in Europe, but there are several hypotheses.

Buschbom J, (2022)

It was initially thought that the disease arrived in the UK on around 2000 trees imported from Holland in February 2012, but it’s now thought to have entered the UK sometime before 2006. Exactly how and when are still not determined.

It’s estimated that 85-90% of Ash trees are expected to die as a result of infection, Click here to see some info from the woodland trust

Identification of Symptoms of Ash Dieback

The first symptom of an infection with Chalara is blackening of the leaves and shoots in mid to late summer, so July to September.

Image from forest research here

Most of the infected leaves are shed by the tree, but in some cases the infection in the leaves, spreads to the twigs, branches and eventually the bark, causing dark lesions or cankers to form in the bark. Often these are characterized by an elongated diamond shape, centered on joints between branches and where branches are joined at the trunk.

Image from forest research here

These lesions can spread up and down the trunk, as the infection spreads and eventually girdle the trunk, cutting off the tree’s supply of fluids and nutrients from the roots. If the lesions aren’t big enough to completely circle the affected stem, they can dry out and crack open, as the tree grows around the damage.

Ecological and Economic Impact

Ash foliage allows light to penetrate to the woodland floor, providing essential light for ground plants and other animals. Several insects, other invertebrates, mosses and lichens depend exclusively on Ash for their survival, with species of moss and lichen in our temperate rainforest of Scotland found nowhere else in the world.

From a commercial perspective, Ash is a strong durable wood with an attractive finish. It has a wide range of uses in joinery, as flooring, furniture, tool handles and sporting goods.

How Does Chalara Dieback Spread?

The spores are dispersed by the wind and can be carried tens of miles from infected areas.

Infection over longer distances is probably through movement of diseased Ash saplings, timber or leaves. It is currently prohibited to import or move across inland, Ash seeds, plants or any other type of Ash planting material.

It’s also thought that the movement of logs or unsawn wood from infected trees may also be a pathway for distribution, but this method of transport is considered low risk.

Playing Our Part In Minimizing The Spread

It’s certainly a challenge preventing the spread of wind borne diseases such as this pathogen, but there is, nevertheless, much that we can do to slow it down and minimise the impact.

When visiting woods, forests, parks and public gardens brush soil, mud, twigs, leaves and other plant debris off footwear and wheels, including the wheels of cars, bikes, baby pushchair and buggies, BEFORE leaving the site. Wash these items once at home, before visiting another similar site.

Park vehicles on hard standing such as tarmac or gravel, as opposed to grass surfaces when visiting such sites.

A lot of mountain biking trails are in forests and mountain bikers are encouraged to use on site wash down facilities that are available at lots of trail centres, before they leave. Also, make sure your bike has been washed down before arrival. This will ensure that Chalara, (or some other pant disease), is not accidentally introduced into that area.

Gardeners, allotment owners and park managers where Ash trees occur in small numbers, can slow the local spread by collecting and burning, (where permitted), burying or deep composting fallen Ash foliage. This disrupts the life cycle of the fungus.

If you decide to compost the leaves, make sure they are covered with a 10cm layer of soil or a 15 to 30cm layer of other plant material, such as kitchen waste. Leave the pile undisturbed for a year, apart from adding more material on top. This will prevent any spore dispersal.

For advice on how to manage infected trees on your own land, the Forestry Commission have published guidance in their 2019 leaflet, Managing Ash Dieback In England, with much of the advice applicable in Scotland, Wales and Ireland.

References.

Jutta Buschbom, Genomic patterns and the evolutionary origin of an invasive fungal pathogen (Hymenoscyphus fraxineus) in Europe, Basic and Applied Ecology, volume 59, March 2022, pages 4-16.

The Impact of Ash Dieback on Veteran and Pollarded Trees in Sweden by Vikki Bengtsson, Anna Stenström and Camilla Finsberg, The Royal Forestry Society, Quarterly Journal of Forestry.