foraging and herbal medicine go hand in glove.

Herbal remedies are easily produced at home because they involve extracting and/or preserving plant material using age-old processes like macerating in vinegar, oil or alcohol, preserved by drying or using a potent source of sugar or salt, or fermenting into a condiment or beverage. Most of these forms are for internal consumption, although some, such as oils, lend themselves to inclusion in topical products like creams, ointments, lotions and balms.

There are two broad ways to think about foraging and herbal medicine for health at home:

1. Tonic Herbs

The tonic herbs in your daily life as teas, in salads or as a particular tonic extract that you add to your daily drink.

This way intends on maintaining robust health and immunity, keeping all systems well oiled.

2. Specific Use

The other way is to use specific herbs for specific ailments, e.g. dabbing dandelion or greater celandine sap on a wart, drinking a chamomile and fennel tea after eating for indigestion, or inhaling hyssop and thyme steam for a chesty cough.

This approach could be called the acute, rather than tonic, approach, and should be used judiciously and usually for conditions that would sort themselves out eventually anyway. If you would like to use plants for health purposes but feel a bit out of your depth and would like more personalised support, get in touch with your local medical herbalist. Both of these domains – the tonic and acute use of herbs – work best if you are foraging for your medicine chest and larder throughout the year, preserving as you go, so that what you need is to hand when you need it.

What is a Herb?

In this article a herb is meant in the functional sense of the word: a plant used for a particular purpose in food and medicine. Any part of a plant can count as a herb; we use the flowers of marigold, the roots of wild valerian and the bark of willow for different purposes. Some plants, for example nettles (and many more than we might expect), are a sort of panacea, offering leaves, seeds, roots and stems of value and use.

Botanically speaking, the term herb refers to herbaceous plants as opposed to woody plants; they have soft stems and completely die back in the winter, although they can be perennial as well as annual.

Tonics

The idea of a tonic is central to both foraging and herbalism: a good thing, done or taken little and often, that keeps a system working at its optimum. The medicinal benefits of the activities of foraging and processing plants are many, and begin as soon as you step out the door and into the fresh air. The mental health benefits of being outdoors, doing something engaged and mindful like gathering plants, are the subject of a whole other article, but the mechanisms are many and the NHS is beginning to carry out ‘Green Prescribing’ given the growing body of evidence.

Foraging and Herbal Medicine Then and Now

Let’s get the classic trope out: “Let your food be your medicine and your medicine be your food,” said Hippocrates. A more modern version, and based on decades of extensive journalistic investigation, is from food journalist Michael Pollan. After tracing food through the industrialised food system from field to fork and comparing it to traditional food ways, his conclusion for how to maintain health through eating is: “Eat food. Mostly plants. Not too much.” By ‘food’, he means real food like vegetables, pulses, fruits and grains, not processed foodstuffs that come in colourful packets and have been highly preserved.

These phrases capture the epitome of the tonic use of herbs as preventative measures. The beauty of foraging for the herbs that you add to your food (as vegetables spices, garnishes or extracts like oil and vinegar) from the wild is threefold: you experiment with flavours and textures you will not find in shops, you benefit from the substantial vitality present in wild plants that allows them to survive in non-cultivated areas and you become more connected and skillful in your local environment.

Herbs have always been available for medicinal purposes

Herbs have always been available for medicinal purposes for both humans and animals (check out zoopharmacognosy), with various peaks in sophistication in different civilisations and empires. Green Pharmacy by Barbara Griggs is a great read on the history of herbalism in the western world.

Plants are still the primary source of medicine for an estimated 80% of the world’s population due to the inequality of biomedical healthcare distribution.

The loss of foraging and home remedy preparation as a commonplace knowledge and skill base has taken place mostly over the last hundred years, but during the world wars there were huge public health campaigns encouraging the harvest of rose hips and conkers, the former used as a source of vitamin C and the latter as livestock food and a source of saponins for soap (if you gather enough conkers you may never need to buy laundry detergent again).

Herbs and Pharmaceuticals

A common misconception is that you need to choose whether you use herbs or pharmaceuticals to treat a health condition. In reality, the rights herbs (check with a healthcare provider, medical herbalists are extensively trained in how to take herbs safely alongside pharmaceutical medications) support other medicines, sometimes making them more effective, and certainly supporting your body to regain background health. Many pharmaceutical chemicals are derived from plant and fungal sources in a process known as pharmacognosy. Aspirin is a modified version of a molecule found in willow and meadowsweet, named for the latter’s old latin name of Spiraea. Statins were isolated from yeasts. Artemisinin, from plants in the Artemisia genus, is one of the most currently researched anti-malarial drugs. In the first and second world wars, British gardeners were enlisted to send vast quantities of toxic plants like foxglove, henbane, woody nightshade and deadly nightshade to synthesise anaesthetic and cardioactive drugs essential for carrying out serious surgery in the field.

Weeds, Glorious Weeds

Some of the best medicines available in the woodlands, meadows and hedgerows also happen to be the most abundant. Take nettle. An amazing accumulator of essential minerals like iron, calcium and magnesium, incredibly safe (providing you protect yourself from stings) for use as a leafy vegetable in relatively large quantities, and great for the urinary tract and the skeleton – two essential systems! The leaves make a delicious ingredient in tea, or star in the show of cream of nettle soup. The seeds are quite stimulating and can be harvested by the handful (who’s going to mind?) for roasting and adding to a granola, cracker or garnish mix. If you are inclined in the textile direction, you can revive the art of extracting the long, strong fibres from mature nettle stems and weaving them into cord and cloth.

Dandelion is a herb and vegetable that we should all be using more

Dandelion is a herb and vegetable that we should all be using more. Just like it’s one of the first to grow on abandoned, compacted soils, and does amazing soil rehabilitation work by introducing pockets of air, microbes and water, it is one of the best general tonics for the human digestive system. Harvest the root in autumn and use it as you would parsnip or carrot. The leaves are chock full of potassium and other minerals drawn up by that long taproot, and can be used as salad and leafy greens. The buds make good capers when pickled, and the flowers are highly antioxidant. Any or all of the parts can be macerated in vinegar or alcohol for a range of taste and use outcomes.

What about Seaweeds in foraging and herbal medicine?

Seaweeds make amazing medicinal foods due to their super high mineral content. In particular they contain iodine in higher amounts than land plants, which is essential for thyroid function, which in turn is essential for the proper metabolism of energy in the human body. Don’t overdo it – everything in little portions, often – but it’s well worth learning to identify a few tasty seaweeds and making it a habit to have them in your diet.

Let’s utilise invasive species in foraging and herbal medicine!

Invasive species in your local area should be top of your list for foraging because nobody will mind you harvesting them! They often offer interesting flavours too. Japanese knotweed shoots can be used like rhubarb, and himalayan balsam seeds, if gathered in quantity and processed appropriately, could supplement the pulse portion of your diet. The medicinal part of eating species like these are the range and rarity of phytochemicals that become available to you which you usually wouldn’t access in farmed foods. Think of it like small challenges for your metabolism to overcome, each time making it more robust and complex. If eating any plant makes you feel unwell, stop immediately. Before you go out and forage, learn about the toxic species and what the signs and symptoms of poinsoning are.

What next?

If you’re excited by the idea of learning more about using herbal remedies, get in touch with your local herbalist who is likely to know how you can go about gaining more skills. And come on a foraging walk with us so you can bump start your use of wild foods in your cooking, bringing in all the vitality and healthful nourishment they have to offer.

2 replies on “Foraging and Herbal Medicine”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

Thank you.

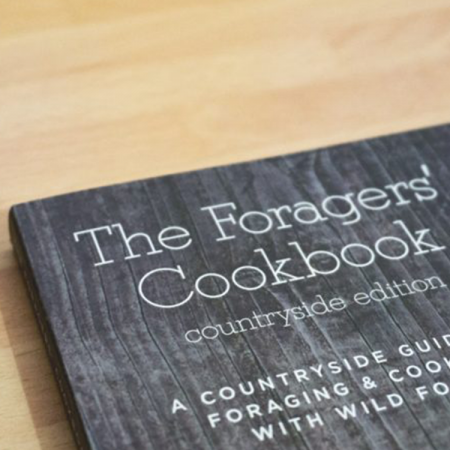

I would like to buy a guide to foraging for medicinal (tonic and acute) purposes with simple recipes and methods.

Are you able to recommend one?

Hey, there’s a book called Wild Remedies which is really nice 🙂